Yu, Jane H. C.

(film critic)

The scope of the 9 films selected for the “Island Odyssey” International Selections program span islands across the globe: New Guinea, Samoa, Sumatra, Madagascar, the Canary Islands, Haiti of Hispaniola, Canada’s Saltspring Island, a Norwegian isle, and the Cape Verde Islands. The material covered is expansive as each film has its own unique theme and serves as a model ethnographic film introducing other cultures.

You Can’t Live With Your Mouth Shut deals with a “butt-shaking ritual” from the Cape Verde Islands. Lucha Canaria-Sport and Identity in the Canary Islands introduces local wrestling. The Poet of Linge Homeland shows us a people of Sumatra moaning chant rituals. The program also displays some works that do not correspond to most viewers’ expectations of ethnographic film. In particular, Elmer and the Flower Boat takes the life of a Norwegian flower farmer and offers a personal sketch of his life while dealing with broader issues of social responsibility all at once. Ah… The Money, The Money, The Money: The Battle for Saltspring describes the long war of resistance that Canada’s Saltspring Island residents have sustained in fighting against capitalists and politicians over forest preservation. Children of Shadows tells of the phenomena of children coming from poor families being sold by their parents to more affluent families who raise them and use them as long-term laborers.

There are some excellent works in this program that deserve to be properly introduced. The film Paradise Bent produced by Australian female director, Heather Croall, has not only secured a measure of significance in the world of ethnographic film but must also be important as an example of research into sexual identity. The work treats as its subject a gender type besides that of male or female generally accepted in Samoan society: fa’afafines are born biologically male, but recognized as female. Croall begins speaking from her own “discovery” in Samoa of this unique gender type. She then goes on to introduce several cases through interviews that allow the viewer to form a special understanding of fa’afafines. Subjects ranging from their normal dress as females and work at home, their emotional affiliations (as they see themselves as female, see each other as sisters, and find male partners, but don’t see themselves as homosexual). Their position in society, and at home, and the dilemma between this custom and foreign cultures (including the drag shows that have been popular recently and the prejudices of heterosexuals towards transvestites…) are presented in the film. Many questions are raised that reach beyond what we learn from the film that may me investigated later when more people continue to focus on this topic. The film also raises the way that past research on Samoa almost totally overlooked the existence of fa’afafines and creates a strong feeling for the blind spots that exist between different ages and societies. It would useful to compare this film with other ethnographic films investigating Samoan society such as Robert Flaherty’s Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age. Also take into account the research written by Margaret Mead on Samoan society as comparative reading.

A film by French director Cesar Paes is a beautiful and moving work entitled Angano Angano… Tales of Madagascar, completed in 1989, is a film that successfully represents the importance of oral history in cultural dissemination. In this island’s history and the living wisdom of society continues to be passed down through the generations by legends, chants, and myths recanted by elders. The film employs interviews with elders and their spoken performances. It starts with the legend of the genesis of Madagascar. It continues by using the elders’ words to tell of individual lives; and the beliefs connected with their ceremonial activities. The film elegantly expresses the intimacy and interdependence of daily life with myth and legend in Madagascar.

Children of Shadows, by veteran American ethnographic filmmaker Karen Kramer, reveals the phenomenon of a house slave trade in Haiti. If some rural farming people are unable to take care of them themselves, they could sell their children to more economically advantaged households. This could happen when the child is about the age of ten. Usually these advantaged households are in the city and the task of the children is doing housework. The subject of this film is reminiscent to the traditional Chinese system of field laborers or the Taiwanese custom of raising future daughter-in-laws in the household as institutional serfdom-a social of societies where the distribution of wealth is terribly unequal. The director seeks to bring forth the perspectives of the people involved through interviews with the traded children, family members receiving them, and the parents of those children sold to avoid leaving the viewer with a one-sided opinion on justice.

This program still holds another film that shouldn’t be missed: Black Harvest. It describes the highly dramatic life of Joe Leahy, the son of a Papua New Guinean and a Caucasian. He lives as a highland coffee plantation owner. Due to the global coffee market trend, his coffee business is not earning as anticipated. The plantation workers both seek to negotiate better pay and courageously enter in other tribe’s battles. The film shows how the tribesmen take up spears to fight in the highlands. The injured are treated by traditional healing arts much the same as it was for their ancestors, centuries ago. The leaders among the employees of the plantation continue to work without stop but haggle with Lai-qiao over the rights and interests of labor and capitalist market system. Old and new value systems are juxtaposed bearing out absurd results revealed in the story of a man existing between two very different cultures.

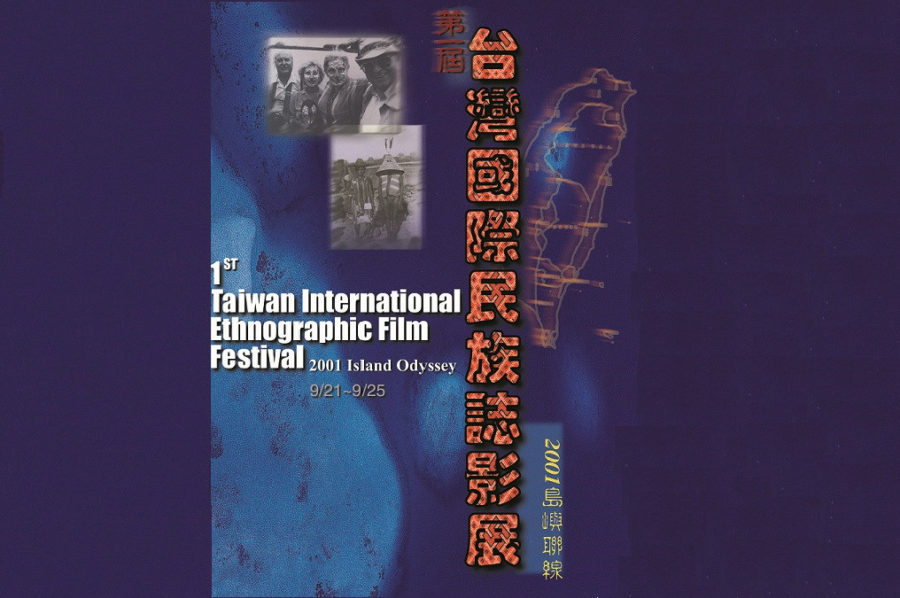

Apart from the film The Poet of Linge Homeland Western directors coming from the deep tradition of ethnographic filmmaking made the other ethnographic films dealing with the islands outside of Europe and America. This bears out the dominating presence of Western society’s history of anthropological study and ethnographic filmmaking. Yet, it is interesting in this regard that among the Taiwan domestic filmmakers of the “Island Odyssey” selection, motion pictures by outsiders and self-filmed ethnographic works are represented. A film shot by Orchid Island’s own people closes the festival showing the importance of the direction coming from self-produced ethnographic films. At the first Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival, the problems in making ethnographic documentary films vis-a-vis their position and outlook will be explored. These films demonstrate the very different sorts of themes and materials presented to help general audiences break free of the narrow view many have of ethnographic film and give broader meaning to the genre.

(Translated by Peter Vlach)