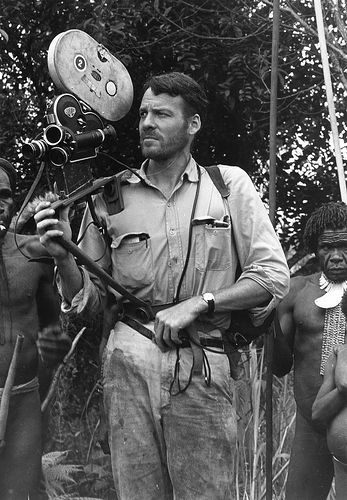

Dead Birds—a classic work in early history of ethnographic film—is about the Dani, a people dwelling in the Grand Valley of the highlands of New Guinea. It was shot in 1961 by Robert Gardner, a famous ethnographic filmmaker with an anthropology background who started shooting and editing ethnographic films and documentaries in the 1950s.

In 1960, the Aboriginal Affairs Minister in Dutch New Guinea went to the United States to attract American anthropologists’ interest in field work in New Guinea. Although the Dani had met western culture, they still used stone tools (for the most part) with a few metal tools in their daily life and frequently had ritualized intertribal warfare with spears and arrows as their weapons. Anthropologists and ethnographic filmmakers of course would not let the chance of witnessing or filming this primitive Stone Age way of life slip away. As an ethnographic filmmaker, Gardner thus organized the Harvard Peabody Expedition, which was comprised of film producers, anthropologists, and naturalists, to conduct research and filming in the challenging cultural environment of New Guinea.

There were very few ethnographic films in western countries before Dead Birds was introduced. The most famous among the few was Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, which set the initial style for the genre—focusing on one or two individuals in the film and presenting the culture of the group through footage of their adventurous life. John Marshall’s The Hunters, another classic in the early period, was produced in the same style. Marshall and his family went off to the Karahari desert in southern Africa in 1951 to study the life and culture of the Ju/’hoansi people. After shooting a vast amount of film he completed the first film of a series–The Hunters–in 1958, of which the subject matter was four Ju/’hoansi men hunting giraffes. As Gardner was involved in the film editing of The Hunters, it was believed that this experience would have certain influence over the style of his later creation of Dead Birds.

When Gardner arrived at the shooting scene in New Guinea, the first thing he did was to look for shooting targets. He found Wejak, a warrior, and Pua, a pig herding boy. He spent plenty of time to build relationships with them and their family and to understand their daily life. He used their daily life stories to form the spine of the film combined with battles and rituals. The name of the film—Dead Birds—was inspired by a fable about the Dani. The story said that there was an argument between a bird and a snake about whether man would die like a bird or would live forever like a snake by shedding its skin. The result was in favor of the bird. Since then, all men must die like birds. The terms “dead birds” or “dead people” in the Dani culture also referred to the spoils of war. In Dead Birds, every episode was recorded based on true events. One day during Gardner’s five month stay in the Grand Valley, some children went to a river and played in water while the tribe was having a rite called wam kanekhe. There were no guardians in the area and they were raided by an enemy tribe, causing one to be killed. Once the funeral for the child was over, people in the tribe killed one person from the enemy tribe for revenge to keep the whole tribe away from the threat of the spiteful spirit.

In fact, Gardner and his Harvard partners, including anthropology graduate Karl G. Heider and naturalist Peter Matthiessen, were conducting ethnographic surveys and shooting the film at the same time. As they knew little about the culture of the Dani, each member of the expedition studied and observed the tribe by themselves during the day and exchanged information and ideas at dinner. When Gardner shot ritual or battle scenes, other members were also on the spot but would avoid being shot by the camera. Although Gardner had considered including the field work process as opening or ending footage of the film, he later decided not to do so. It’s a pity that this decision took away the reflexive angle to the film.

In Dead Birds, there is a ten-minute footage of the child’s funeral. One of the Dani customs was that when one person was killed by an enemy the tribe needed to hold a ritual of “fresh blood”. Hundreds of villagers would gather together, and show and exchange a great deal of pigs, fishing nets and cowry shells to pacify the ghosts, especially the spirit of the dead. The film showed a crowd of people sharing things such as cowry shells, preparing the body, burning the woodpile, and holding a ceremony to free the spirit of the dead from the body and send it to the forest. The film production team did not understand the Dani’s culture well and therefore put the emphasis on the emotions around death and the ceremony. Both the images and the sounds, the facial expressions of different individuals in particular, accentuated the atmosphere of mourning and grief. However, the more important part in the one-day funeral, later discovered by Heider, was the interaction between villagers, e.g. greetings, gift exchanging, gossiping, and offering sharing. In every interaction the Dani would appropriately express specific emotions. The film should have focused on the subtle interactions and emotional changes among the Dani to convey ethnographic knowledge more accurately. Of course, Dead Birds did not falsely portray the basic ethnological facts of the funeral (e.g. economic exchange behavior, symbolism, belief in ghosts). The focus of the film in fact reflected the trend of academic training studying anthropology in the 1950s. However, as interaction theory and emotional behaviors have got more and more attention from anthropologists, Gardner would definitely use a different approach to shoot the subject of Dead Birds, if he had another chance.

Dead Birds was produced in 1961 when photographic and sound recording equipment was going through major changes. Long takes became possible and therefore added into the film a flavor of contemporary documentary similar to “cinema verite”, a newly-developed style of film-making at that time. An Arriflex 16mm camera with a magazine holding 400 feet of film, together with a self-made battery, was used for Gardner to shoot a 12-minute sequence, non-stop. It might sound like a significant obstacle instead of an advantage compared with today’s digital cameras which support 2 hours of constant shooting. However, it should be known that before 1960 most motion picture cameras could only take shots of no more than 3 minutes, causing every shot to be very short and making long following shots impossible. Hence, what Gardner achieved in Dead Birds was indeed a milestone in ethnographic film history. Unfortunately, a synchronized sound track was still unachievable at that time. Sounds had to be recorded by Michael Rockefeller, the sound recordist, for post-synchronization. (Yes! He was the youngest son of the former US vice president Nelson Rockefeller who disappeared in southern New Guinea during the study of the Asmat.) In addition, a great deal of narrative monologues were used by Gardner in order to construct the overall narrative structure and to help develop a classic story line—beginning, conflicts, rising actions, turning points, climax, and ending. And it is the usage of the monologue and the dramatic structure that is most often criticized. Gardner would narrate monologues in the present tense to tell viewers what the principals were thinking and the deep philosophical thoughts which the Dani had about death.

In this regard, many anthropologists have harshly criticized the film. Craig Mishler’s criticism may be the strongest among them all. He said, “My judgment is that Dead Birds has been colored by so many subtle fictional pretensions and artistic ornamentations that it has surrendered most of its usefulness as a socially scientific document.” However, David MacDougall thought that Dead Birds was not designed and did not only present the subjective view of the Dani clan. He believed that the film, more importantly, was to reveal issues which human beings had to face immediately. For example, the scene of ritualized battle was to encourage the viewers to contemplate warfare from a different angle while developing a sense of identification with people in other societies through the film. In other words, MacDougall believed that Gardner was trying to philosophize about death and violence by interpreting the Dani experience through mythology, a form of traditional literature. This was the reason that Gardner used some old sayings or even rhymed monologues in poetic form to describe the Dani’s interior thoughts. The usage of monologues in the present tense, from MacDougall’s perspective, created a legendary atmosphere, effects of fable and metaphor, and a more intimate feeling. An example of a monologue is, “This scene always cheers him up even when he thinks about the enemy’s plan of attack.” In MacDougall opinion, applying traditional literature was a style that went beyond what filmmakers would then typically choose. Nor was it used by humanists. Yet Gardner’s approach may be more persuasive 30 years after Dead Birds was first introduced, when various experiments are now being made widely. In short, MacDougall thinks there are a couple of things worth paying attention to: (1) bringing Dani myth into the film marks the beginning of using literary materials to explain human behaviors in ethnographic films; (2) the approach taken in Dead Birds matches the thought of some anthropologists who want to use experiences in other societies to criticize their own culture.

When Gardner was about to finish the production of Dead Birds, he moved his “Film Study Center” from the Peabody Museum to Harvard’s newly established visual arts center to undertake education and training in ethnographic film and filmmaking. It was unfortunate that the Film Study Center was not able to build a partnership with the anthropology department of Harvard to co-develop the theory and practice of ethnographic film. Gardner later started production of other ethnographic films. The subjects of his films include African nomads, Indians, and Columbian aborigines. In his later works, he gradually took away the monologues and directly used images as a means of communication. Although his films seem to be in the form of realism, or even ethnography, they are indeed anti-realist and closer to symbolism. When he was shooting different cultures, he was reluctant to “responsibly” explain these cultures like average anthropologists. As his films prevail, Gardner has been regarded as an influential and controversial heavyweight by western anthropologists. And it is no doubt that a variety of topics inspired by his works will continue to be raised, discussed, and debated.

Reference

Devereaux, Leslie and Hillman, Roger, ed. (1995). Fields of Vision: Essays in Film Studies, Visual Anthropology, and Photography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Heider, Karl G. (1976). Ethnographic Film. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Heider, Karl G. (2004). Seeing Anthropology: Cultural Anthropology through Film (Third Edition). Boston: Pearson Education.

Loizos, Peter (1993). Innovation in ethnographic film: From innocence to self-consciousness, 1955-1985. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

MacDougall, David (1998). Transcultural Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press.