Introduction to the Three Films from the Program “Formosa Aboriginal News Magazine” on Taiwan Indigenous TV in the 2007 Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival

Cheng-liang TSAI

Ph.D.Student

The Institute of Anthropology, National Tsing Hua University

Seeing is a simple enough concept, but

seeing without understanding is not truly seeing,

seeing without appreciating is not truly seeing,

seeing without respecting is not truly seeing.

Taiwan’s indigenous peoples expect to be truly understood, truly appreciated, and truly respected

They expect that Taiwan can truly SEE the world of the island’s indigenous peoples.

─ Taiwan Indigenous TV【TITV Weekly】

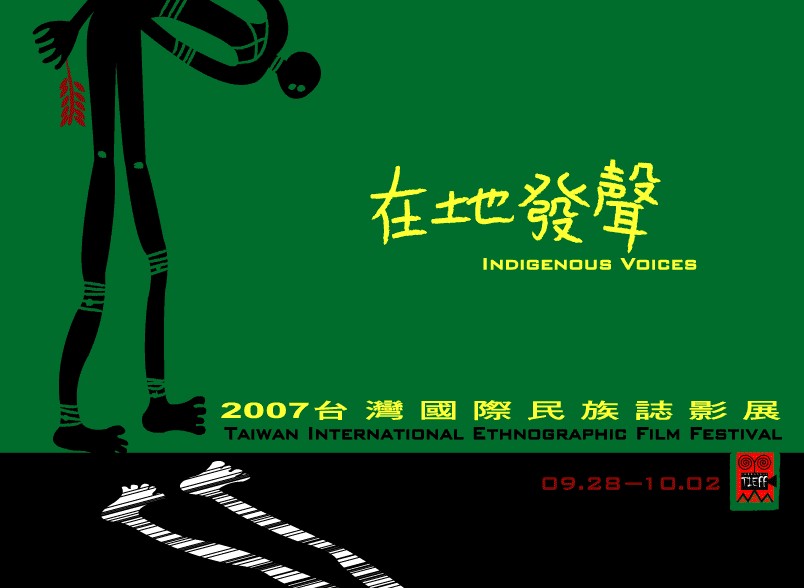

The theme of the 2007 Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival is Indigenous Voices. Three of the selected films for this year’s festival were originally broadcast as part of the program “Formosa Aboriginal News Magazine” on Taiwan Indigenous TV (TITV, Asia’s first exclusively aboriginal television network): 《When the Village Encounters the Country》by Pisuy Masou and Vikung LaLegeam,《Conversation of Tali and Yaki》by Halugu Watan (Chang Shu-min), and《Retrospect Days of White Terrors》by Pisuy Silan and Kaleh Kalahe (Kao Chih-chang). These three films, all helmed by aboriginal producers, show how Taiwan’s indigenous peoples are stuck between the past, their current reality, and visions of the future. They feature stories that were overlooked by Taiwan’s mainstream media. While each film may express distinct viewpoints and utilize different techniques, they all share a common sentiment. The viewer can hear a voice urgently struggling to free itself from the space between the present, past, and future. The filmmakers attempt to bring these often untold stories out into the light, which is also the goal of TITV. The station endeavors to expose society to Taiwan’s aborigines, so that people can understand, appreciate, and respect them, so that Taiwan can truly SEE the world of the island’s indigenous peoples. These three films are told in aborigines’ own words, which convey an eagerness to be truly seen by the world.

《When the Village Encounters the Country》

In its short running time of 28 minutes, this film is able to directly, strongly, and completely portray a case of government sanctioned violence. Different from usual news reports, which are purposely unbiased, this story is told from the point of view of the Taiya people, who denounce the unjust national violence and the government’s slow pace to make amends.

This film portrays the story of three Taiya tribe members, all residents of the Semakuse village in Hsinchu. Following a typhoon, beech trees were uprooted by the storm on what they consider to be Taiya land. After a tribal meeting, the three men decided to bring the fallen trees back to the village, as is customary. However, the Forestry Bureau saw this as stealing national property, and took the men to court for breaking Forest Law. The men were sentenced to six months in prison or a fine of NT$160,000 and two years probation. In hopes of overturning the verdict, the Taiya people in Semakuse launched an appeal, which is still pending in the courts.

The director uses traditional Taiya songs to narrate the film, with vocalist Yi Chen (the head of the Taiya people in Semakuse) expressing the anger and frustration of the Taiya people in Semakuse through song. The traditional chanting paired with the film’s images show the depth of understanding the aboriginal film producers have towards their own culture. Using this unique storytelling technique, it is as if the directors raise up a Taiya headhunting knife high above their heads and scream out against this unjust government-sanctioned violence.

The film cannot be considered a news report in the traditional sense, because it is clear that the filmmakers side with the villagers. As an independent, autonomous aboriginal television station, TITV aims to serve not just as a news source, but as an arena for the island’s indigenous peoples to express their own viewpoints, when for so long, society at large was completely devoid of their voices. Such films want more than to simply show the world of Taiwanese aborigines, but seek understanding from the outside world. By featuring these three selections at this year’s Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival, TITV can reach a larger audience and expose the problems that have occurred when strong and weak groups have collided throughout Taiwan’s history.

《Conversation of Tali and Yaki》

Unlike “When the Village Encounters the Country”, the film “Conversation of Tali and Yaki” is not a strong indictment of the unjustness that occurs when tradition meets modernity, but it has a kind of inescapable sadness.

Tali and Yaki of the film’s title are members of the Taiya tribe, one young and one old, who have never met. By contrasting their experiences living in different eras, the film portrays the Taiya identity and expresses the struggles, frustrations, and courage of its people. Despite the opposition of other tribe members, young Tali seeks out a Han Chinese tattoo artist to give him a traditional Taiya facial tattoo, which have all but disappeared in modern times. He simply wishes to become a true Taiya person, even influencing his wife and children to help him bring back this tradition, together bravely reclaiming the self-identity of the Taiya. Yaki, on the other hand, is nearly 80 years old. She and Tali have never met, but they have something in common. She might be the last person living to have received a tribally performed facial tattoo. However, it pains her to remember how her parents forced her to get the tattoo as a young girl. Tali’s opinions about the tradition concern and reassure her at the same time. By contrasting the stories of Tali and Yaki, the film conveys the contradictory emotions the Taiya people have felt towards facial tattooing over the years and the conflict between tradition and modernity.

The purpose of the film is not simply to praise Tali for courageously carrying on the tradition while facing pressures from modern society. The director’s technique portrays the struggles, frustrations, and courage of the Taiya, who are caught between their traditions and the modern world. The director clearly knows that if his film just bemoaned the loss of tradition, it could not accurately portray the lives of contemporary Taiya people and their emotions about the facial tattoo tradition. By interweaving the stories told by Tali and Yaki, he skillfully illustrates how tradition and modernity have both conflicted and blended together. The two Taiya are members of different generations who have lived through very different periods in the tribe’s history, but their lives portray the frustration and courage shown by the Taiya as they face the progression of history. These aboriginal filmmakers are not simply using their films to condemn the loss of tradition, but hope to portray a more complete story of the problems and situations that aborigines face living in the modern world.

《Retrospect Days of White Terror》

While “Conversation of Tali and Yaki” portrays a story of contemporary aboriginal people, “Retrospect Days of White Terror” seeks to retrace history and uncover a story that has nearly been forgotten, the story of the ultimate sacrifice made by early aboriginal leaders Lin Jui-chang and Kao Yi-sheng during Taiwan’s White Terror.

When people discuss the White Terror or the February 28 Incident, they rarely think beyond the conflict that occurred within Han Chinese society. This film tries to sketch in events that occurred during that period, like the sacrifice of these two men, which have been omitted from the history books. The movement to recover traditional names and the land claim movement are generally seen as the initial stirrings of the aboriginal political movement. “Retrospect Days of White Terror”, however, claims that the movement began much earlier, with the sacrifices of Lin Jui-chang (Taiya), Lin Chao-ming (Taiya), Kao Yi-sheng (Tsou) and Tang Shou-jen (Tsou) that paved the way for the next generation of leaders.

It brings to light a long forgotten tragedy that had slipped through the cracks. The filmmakers show that the aboriginal political movement can be traced much further back than most people realize. Taiwan’s aborigines did not wait until the 1980’s, as is often believed, before they began to resist the government that had for so long violated their rights.

Telling Their Own Stories to the World: Taiwan Indigenous TV

The excellent filmmakers who produced these works are also employees of TITV, which first broadcast the three selected films. These stories were saved from oblivion to be enjoyed and understood by the greater Taiwanese society. Although it has been a difficult road for TITV after its founding more than two years ago, more and more talented aborigines are joining its ranks and its operations are getting on track. TITV’s programs are increasingly diverse, but it is still guided by its core principle: to show Taiwan’s society the true aboriginal experience that has long been ignored.

These indigenous filmmakers open a window through which those outside can truly see their world.